Prescribed burning is no simple task. It involves precise planning, quick decision-making, and an understanding of any and all potential dangers. Those that plan and execute burns are as creative as they are careful, and have an awareness of fire’s behavior that can only be acquired through dedicated education and experience. If you’re interested in the process of burning, we hope this page can help you understand the behind the scenes work that makes a prescribed fire possible, and what you can do to get involved.

Step 1: Assessing need

Before a burn manager even thinks about putting fire on the ground, there has to be a specific need for it. Fire is a potent tool for ecological restoration that can be used for a myriad of things, including habitat restoration, invasive species management, and fuel reduction. Natural resource managers and fire management specialists will assess their land to see if it warrants burning, which depends on a variety of factors, including habitat type, recent burn history, and demographic of the surrounding area (burning near a hospital or behind an elementary school is very rare). Habitats like Oak Savannahs and Tallgrass Prairies are what we call “fire-dependent ecosystems”, which means that without the presence of fire, they can disappear. Some fire-dependent ecosystems need to be burned every few years, while others need burn only every decade. Once a fire management specialist has decided that an area could benefit from a burn, they must then make sure they have the resources necessary to carry out the burn safely and effectively.

Step 2: acquiring resources

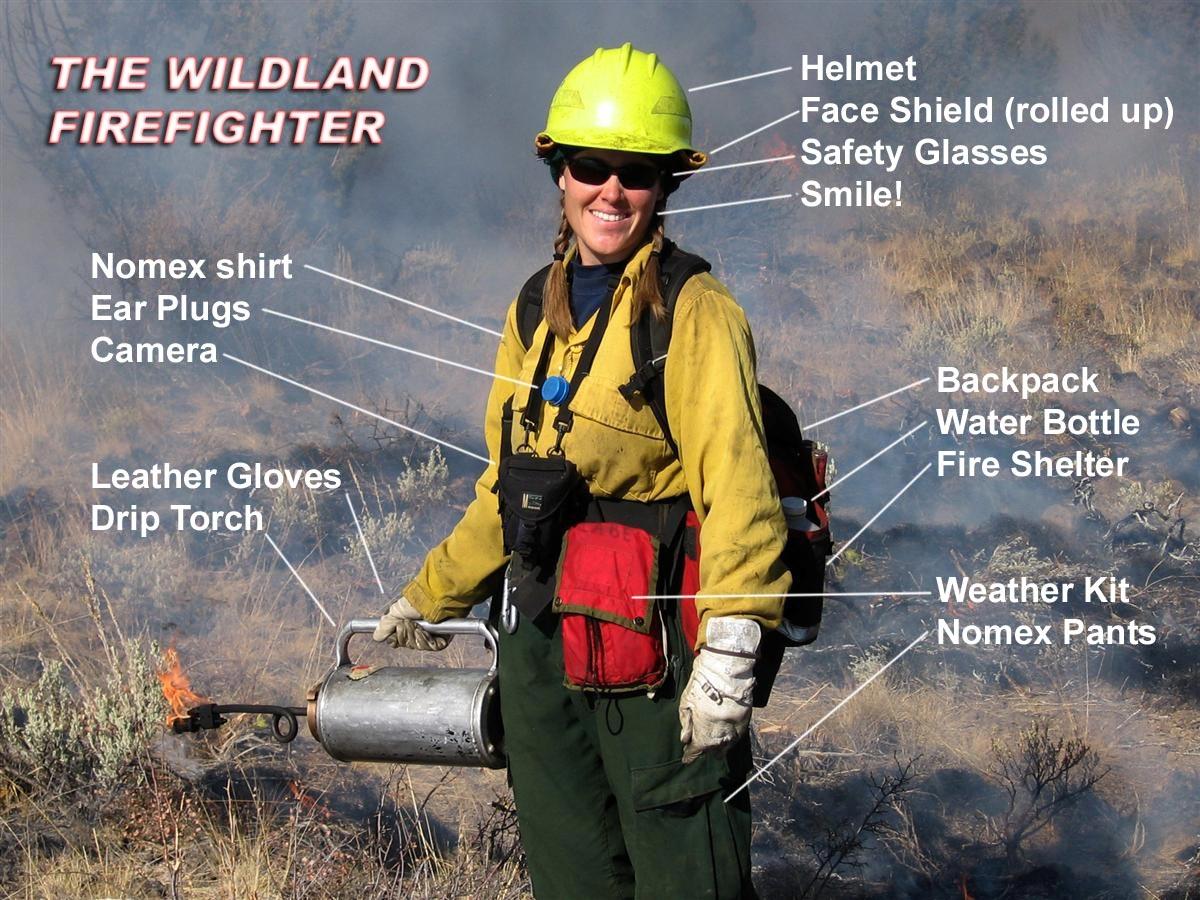

Once a need has been identified, it’s up to those identifying the need to ensure that they have the resources to make burning possible. This includes fire-specific equipment and trained personnel, as well as funding to ensure both of those resources can be acquired. The equipment on a burn usually includes items for ignition (drip torches, fusees), items for suppression (hand pumps, pump trucks), and personal protective equipment (PPE) for all participating in the fire. Well-funded burn programs often have trucks fitted with water pumps, as well as special wildland fire trucks called brush trucks, that are designed to quickly put out any lingering fires. After the leader of a burn program (ideally a burn boss) is certain they have the proper resources to carry out the burn, they can begin planning their burn.

Step 3: planning the burn

Once a plot of land has been deemed burn-worthy, the burn boss will begin to assess the plot. This involves examining the topography, the fuel types (grasses, brushes, slash piles), and the local ecology. The burn boss then uses this data to determine what the ideal conditions for their burn should be, so that when the right day comes along, they can have a prescribed fire that gets them the effects they want, while remaining safe. A large part of planning a burn has to do with making sure the relative humidity (RH) is low enough to allow fuels to catch, while not being so low that their flammability becomes dangerous. Moisture is a huge player in burn planning, and affects everything from the ability to ignite your fuels to the amount of smoke a unit will send into the surrounding area. Many burn bosses use advanced software to see what kind of smoke their fire will put out, factoring in things like fuel type, size of the unit, and air temperature. Public safety is the most important part of a burn, and a good burn boss won’t burn if there’s any chance that their fire’s smoke (or the fire itself) could cause discomfort or danger to those in the surrounding area. Once the burn is fully planned and the fire season is upon us, the boss will plan a day for the burn, one with conditions that favor a productive and safe fire. Members of the crew can be given as short as a day’s notice to get out to a site, depending on how suddenly the conditions shift in favor of a good burn. Once the burn boss has planned a date, the crew will assemble at the site on that day, ready to burn.

Step 4: Permissions and public outreach

Before a burn can occur, a burn boss must get permission from a variety of authorities in the area, ranging from the fire chiefs of the surrounding counties, to the heads of the nearby airports. The specific laws surrounding getting permission to burn vary from state to state, and from county to county, so every burn boss has a different protocol they have to follow before starting a burn. It’s also a good idea to let the 911 dispatcher in the area know that a burn is occurring, since concerned citizens will frequently mistake the smoke from a prescribed fire for smoke from a dangerous wildfire. From time to time, news crews will catch wind of a prescribed fire, and will be on the scene to interview those involved in the burn, either before or after they’ve completed their work for the day.

Step 5: The burn

Now that the planning has been completed, the equipment has been gathered, and the crew is assembled and ready to burn, it’s time to start the burn. The burn boss will begin the day by assigning one person with the task of examining the unit, to ensure everything is as it was when previously scouted. Another person is tasked with recording weather, by checking temperature, wind speed, and relative humidity. While weather is being taken, the crew puts on their PPE, and begins preparing the day’s equipment, filling drip torches with fuel, pumps with water, and getting radios and hand tools ready for action. Once weather is confirmed to be good for a burn, the boss will gather the crew to brief them on the burn narrative. This is the desired course of events for how the burn will play out, which the boss runs through with the help of a map. The boss will also review any potential dangers, what to do in case of any emergencies, and the estimated time of completion for the burn. The boss then divides the crew up into squads, usually two for ignition, and two or more for suppression. Then it’s go time! The ignition crew lights their drip torches and begins igniting the unit, while suppression crews follow behind to ensure the fire remains within the burn unit. If everything goes to plan, the ignition squad makes their way around the perimeter of the entire unit, gets the interior of the unit to burn, and monitors the fire, as suppression crews keep the edges of the unit secure. Suppression crews look for any embers that have drifted to adjacent units and caught fire, as well as making sure any heavy fuels on the edge of the burnt plot are safely extinguished, or are far enough inside the unit to not be a concern. After the unit is secure, the crew reconvenes to go over what happened in the burn, doing what we call and After Action Review (AAR). The purpose of the AAR is analyze what went well, what went poorly, and overall, how well objectives were met. Once the AAR has concluded, the crew will collect their tools, remove their PPE, and head home.

Step 6: post-fire Monitoring

Over the next few days, the burn boss (or designated fire monitor) will return to the site of the burn to ensure it hasn’t escaped, and to examine the impact of the burn. Ideally monitoring will continue for the next few months, even years, to try to understand the intensity and effectiveness of the burn, and to see if it had the desired effects on the burned habitat. While monitoring continues, bosses will begin to assess their unit, to see when it could benefit from another burn. And the cycle begins again from step 1.

Want to learn more?

Come to an MPFC meeting! We’re more than happy to talk to you about any questions you might have related to burning. You can check our Events page to see when we’re having our next meeting. You can also go to our Training page if you’re curious in getting the training that would allow you to get on the fire line.

There are also loads of volunteer opportunities across the state of Michigan to get you on the fire line. Most organizations prefer S130/190 certification, but in many cases it is not necessary in order to participate in a burn. Below is a list of a few Michigan-based organizations that utilize prescribed fire. If you’re interested in volunteering on a controlled burn, you can reach out to the listed contacts and inquire about their burn schedules, as well as any training they may require for volunteers that join them on prescribed fires.